Facilitated by Kyrgyz-based journalist, Sahira Nazarova, our group met to talk about a topic that is important to each of us. Our group included Aleksandr Pugachev, Nadejda Sharonova, Tolkun Ergeshov and Danil Nikitin, all who were involved in multiple trainings with police staff arranged as a part of the WINGS of Hope project. Aleksandr Pugachev is a Co-Director with the GLORI Foundation, Nadejda Sharonova is the Director of the Podruga Foundation in the south of Kyrgyzstan, and Tolkun Ergeshov is a Lieutenant-colonel who heads the Department of Professional Development at Osh Regional Police Authority. Danil Nikitin heads the Bishkek-based office of GLORI Foundation.

Sahira Nazarova: Thanks to civil society’s efforts and well organized global women’s movements, the stereotypical image of a victimized woman exposed to many risks is being changed, slowly but surely, by another type of woman who can stand for her rights. Last year a new domestic violence law and accompanying legislation was signed in Kyrgyzstan. People start understanding that violence against women means violation of basic human rights and will have consequences to the abuser. However, for women who use drugs, the situation is not that positive – do you agree with that?

Nadejda Sharonova: Yes, women who use drugs or who are involved in sex work, or both, do suffer from multiple discrimination. Spouses or parents see beatings, humiliation, or other forms of abuse as deserved or a way to “cure” women from their addiction. What would a regular woman do if she experiences or is under risk of violence? Right, they call police. However, this mechanism is hardly applicable to women from socially disadvantaged groups which include women who use drugs, sex workers or with a history of incarceration.

Aleksandr Pugachev: Judging from our experience, it is important to create alternative protective frameworks for such women at risk of gender-based violence. The most effective help can be provided in community-based organizations where women have the opportunity to speak with their peers who better understand their issues and can provide with feasible advice or practical help. Collaboratively, they can figure out what to do.

Sahira Nazarova: Nadejda mentioned discrimination towards women who use drugs and sex workers. We know that Podruga Foundation conduct trainings with police regarding human rights, tolerance and various aspects regarding international best policing practices. How do these trainings impact the situation with vulnerable women?

Danil Nikitin: Our trainings have helped not just establish collaboration between these community-based organizations and law enforcement agencies, but also strengthen the collaboration. Currently, police are torn by a dilemma, that is, they are often both the first responders to reports of domestic violence and the frontline enforcers of the war on drugs. If we strengthen their role as responders who are aware of national legislation focusing on gender equality and GBV prevention, international agreements ratified by Kyrgyz Government, and other countries’ successful anti-GBV experience, we have a chance to positively impact the health and human rights environment for vulnerable groups.

Nadejda Sharonova: Through trainings we try to strengthen police response in addressing violence toward women who use substances, women who provide sex services, and sexual minorities in Kyrgyzstan.

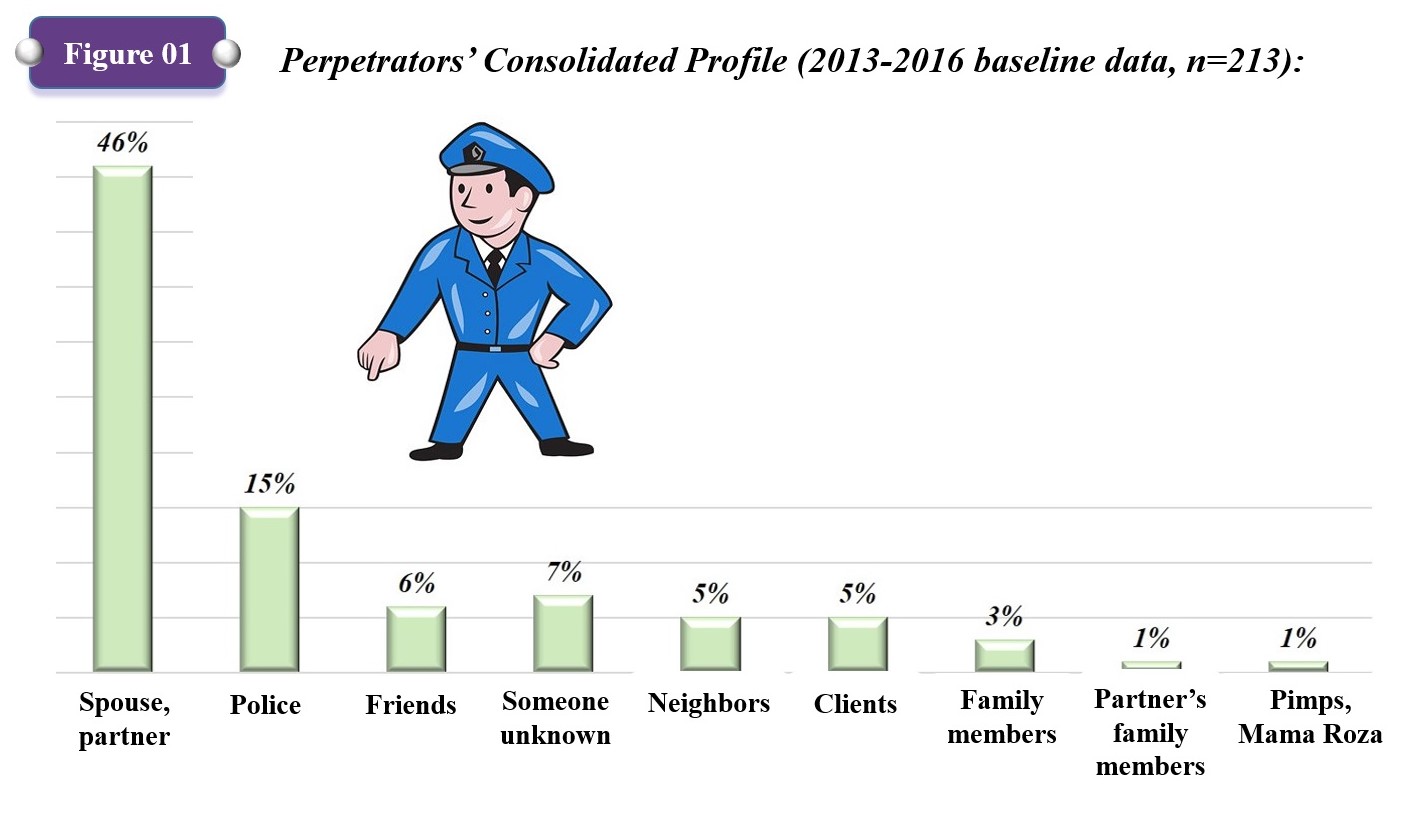

Aleksandr Pugachev: The idea of the trainings with police came to us after we found out that police officers were reported as perpetrators by 15% of the WINGS of Hope project participants. In the participants’ stories of police violence that they shared with intervention facilitators, women mentioned episodes of verbal abuse, money extortion, unlawful detention, intimidation, blackmailing, beating and other illegal actions by the ones who were supposed to provide women with support and protection. In their stories women used such descriptions as “lawlessness”, “forced strip off”, “chained with handcuffs to the heater and left unattended for the whole day”, “forced me to walk naked”, “offended using dirty words”, “threatened to create podstava (accusation based on fake testimonies)”, and others.

Danil Nikitin: A few words about the unique WINGS of Hope. This project is designed to prevent Gender Based Violence (GBV) among women who use drugs, and women involved in sex work. It is important to realize that sometimes people use drugs to cope with a whole range of issues associated with the gender-based violence they are experiencing. Data from Year One of the WINGS of Hope pilot project underscored the need for evidence-based trainings to improve police knowledge, response to, and accountability for GBV cases, including violence by unlawful police officers many of whom are dismissed now. The urgent was a need to enhance cooperation between police and civil society. It was, therefore, suggested to design and manage series of Train-the-Trainer (ToT) trainings with police officers who are responsible for education and professional trainings in their departments.

Sahira Nazarova: How difficult was it to you at NGOs to coordinate trainings with police, and so greatly engage the police staff in the trainings?

Nadejda Sharonova: Working at a government agency, or an NGO, or at an international entity, we all remain citizens of this country, live here and work all together to make this country better. Women who use drugs and women engaged in sex work remain the most vulnerable to multiple forms of violence. Violence against these groups is systemic and perpetrated by individuals and some government agencies’ staff, including police. The existing programs for changing behavioral stereotypes and developing negative attitude towards violence by government agencies, local communities and the victims’ social network, are limited and not sustainable. Simply saying, we identified this gap, and decided to bridge it.

Tolkun Ergeshov: Let me remind everyone that according to the law the police officer’s primary mission is the protection of people’s rights and providing them with services regardless of their background, behavioral specifics or other factors. In 2009, the government initiated a police training program focused on vulnerable populations, but subsequent evaluation showed large gaps in implementation.

Aleksandr Pugachev: The training agenda was designed with involvement of our partner organizations, all members of the No Violence Coalition (NOVIC), including international consultants Luisa Gilbert, Tina Jiwatram-Negron and Timothy Hunt, police experts, and instructors at the Police Academy. Violence by law enforcement officers is one of the reasons for the mistrust of women towards state officials and their unwillingness to appeal for police help in case of violence. Thus, only 8% of the project participants in 2013, 2% in 2014, and 6% in 2016, called police after they experienced episodes of violence, and these were episodes that the participants considered the most traumatic, severe, and that which affected them the most.

Tolkun Ergeshov: As we see from the WINGS of Hope project reports, we have to work harder in order to improve practical implementation of many police guidelines on how we have to respond to the cases of violence. Yes, we have to be prepared to the fact that some of those cases are committed by our colleagues, and when we investigate their unlawful experience, the police leadership will need to fire them without hesitation. We need more such trainings and to have them be conducted more often because our staff rotates and because new laws and regulations appear. Additionally, many new practices are implemented around the world that our police officers would love to be aware of and then apply in their everyday practice.

Danil Nikitin: At all stages, police officers were actively involved in designing the training agenda and implementation. The agenda allows trainees to refresh their knowledge of national legislation focusing on gender equality and GBV prevention, international agreements ratified by Kyrgyz Government, and other countries’ successful anti-GBV experience. The trainees have a chance to review and interpret the “Wheel of Power and Control”, which is an assessment and training tool, specified to the needs of women who use drugs and women engaged in sex trading. They also participate in demonstration sessions on processing victims’ applications for protective orders.

Nadejda Sharonova: The trainings are a relevant platform for open discussion of further collaboration between police and civil society in building a society free of violence and unlawful detentions.

Partner NGOs, while co-facilitating sessions, share with police trainees their experience on drug users’ social inclusion and provided methodological guidelines on specifics of police interaction with women who suffer from violence and are also exposed to multiple forms of discrimination.

Sahira Nazarova: Were the trainings beneficial to vulnerable women?

Aleksandr Pugachev: Yes. Feedback from trainees was used to further enhance safety planning, which is a key component of the WINGS intervention and SBIRT model. SBIRT stands for Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment. It includes a short educational course, where women are trained about the specifics of particular type of gender-based violence; a screening to identify the level of victimization and measure the risk of becoming the victim of violence; intervention aimed at motivating and improving the participant’s emotional state, developing the safety plan; and referral to appropriate service-providers, setting goals for the nearest future, and providing opportunity for HIV test with gender-specific counselling. The enhanced safety planning framework makes the whole WINGS intervention much more effective and therefore beneficial to the participants.

Nadejda Sharonova: Currently, police staff are more tolerant of injection drug users (IDUs) than they were a decade ago. From our experience listening to women at our NGO, in the years past some police used to treat IDU as less than human and not worthy of universal fairness and human rights.

We had the experience where someone told a police officer that IDU, “are people too”, the reply was, “What are you talking about? These are drug users and prostitutes, NOT human beings”.

This is why it was decided to first change the police attitude towards IDUs to include that IDU have an illness, that is, drug addiction, based on the belief that “even if you don’t consider them human beings, you can hardly doubt that they are sick beings”.

In the country we achieved certain empathy towards IDUs but unfortunately attitude towards sex workers is still negative.

Police, where males prevail, are rather reluctant about acknowledging their human rights due to nature of their sex work engagement.

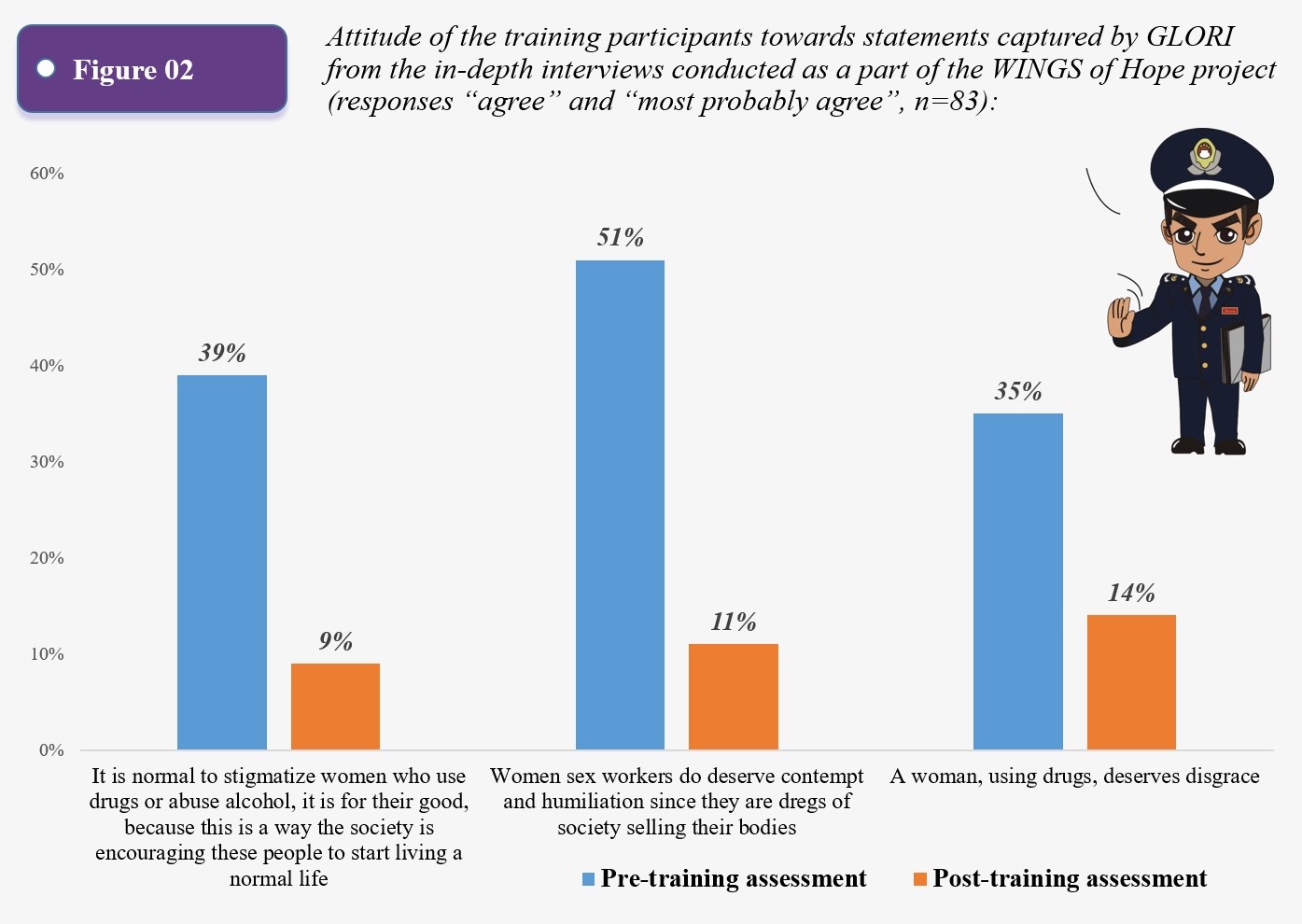

Aleksandr Pugachev: To evaluate the police trainings, we used a repeated survey measure, prior to training and immediately after it.

We assessed knowledge of GBV-specific legislation, attitudes towards women who use drugs, and female sex workers, policing practices in responding to GBV incidents, and the trainees’ commitment to prosecuting GBV cases.

Before the training started, we measured the trainees’ attitude towards these two groups and unfortunately, it was not very tolerant (see Figure 2).

Many trainees reported believing that stigma towards drug-using women is the norm and that drug users and sex workers deserve disgrace. Fortunately, the attitude and beliefs significantly improved at the follow-up assessment.

Sahira Nazarova: Is this situation so bad only in Kyrgyzstan?

Danil Nikitin: No, not only here. In more developed countries police abuse also does exist. There is, for example, a study by US-based researcher, Linda Cottler, where she and her team conducted a study from 2005-2008 in a large U.S. city – in St Louis, Missouri. The participants were women who aged 18 years or older, were under the supervision of a probation or parole officer for a nonviolent offense, and planned to remain in the St Louis area for at least 12 months. At baseline, 78 (25%) of the 318 respondents reported having traded sex for favors with a police officer. Participants reported trading sex with a police officer when they were as young as 15 years.

Among these 78 women, nearly all (96%) reported having sex with an officer while the officer was on duty; 24% traded sex with an officer while he was on duty and in the presence of another officer. Most of these participants reported trading sex with the same officer on more than 1 occasion (77%); about half (49%) did not always use a condom during sex with a police officer. More than half (54%) reported that an officer promised not to arrest or charge them with a crime if they would have sex with him. According to 87% of women, the officer always adhered to this promise.

A total of 31% of the women characterized an encounter with a police officer as rape. I do believe the police need oversight, like public control in all countries, regardless to the country’s economy status. One type of public oversight are Community Advisory Groups such as one we had with NOVIC and WINGS of Hope.

Aleksandr Pugachev: Yes, establishing and strengthening Community Advisory Boards seem to be a feasible solution. These boards include representatives from various strata of the society and serve as liaison between communities and the Government authorities, and also other advisory roles. I also want to make the point that our trainings are supported by the Minister of Internal Affairs, as we know from UNAIDS reports that women who have experienced violence are up to three times more likely to be infected with HIV than those who have not. As injection drug use and sex workers are at higher risk for HIV, this enhances our collaboration with the Ministry of Health and other organizations focused on HIV/AIDS.

Tolkun Ergeshov: In the beginning, we worried that police staff will be reluctant to discuss the sensitive GBV information but now see that the officers are well engaged and openly discuss the issue and propose solutions. I also want to make the point that the individual trainees participating in the WINGS of Hope Trainings, are very much committed to sharing the information that they learn from facilitators, with their colleagues. A police officer is a representative of the state and power and people expect from them support and consider them as defenders. This includes all people – all, including the ones from vulnerable social groups. With the Podruga Foundation, we continue to arrange such trainings in the south of Kyrgyzstan.

Aleksandr Pugachev: According to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the United Nations in 1948, after the Second World War, “All human beings are born free (…)”. This sentence forms the beginning of the Declaration and serves as a classic example of the liberal statement that human beings are born free and have certain rights throughout their lives.

Danil Nikitin: People are free, by default — everyone, including men and women belonging to the most disadvantaged and marginalized groups have every right to be covered by and benefit from social protection systems without discrimination. When existing policies and infrastructure do not support this idea in its entirety, then people have to further develop them to make them freedom-friendly.

We should all work together to strengthen commitment to those universal rules and to ensure that society knows how help individuals whose rights get violated.

Many thanks to Anne (Brisson) Malin, one of the GLORI Foundation’s Senior Consultants, who helped us with editing the text.

Sahira Nazarova (nazarova.kg@gmail.com)

Tolkun Ergeshov (tolkun0109@mail.ru)

Aleksandr Pugachev (aleksandr.i.pugachev@gmail.com)

Nadejda Sharonova (podruga_osh@mail.ru)

Danil Nikitin (danilst.nikitin@gmail.com)