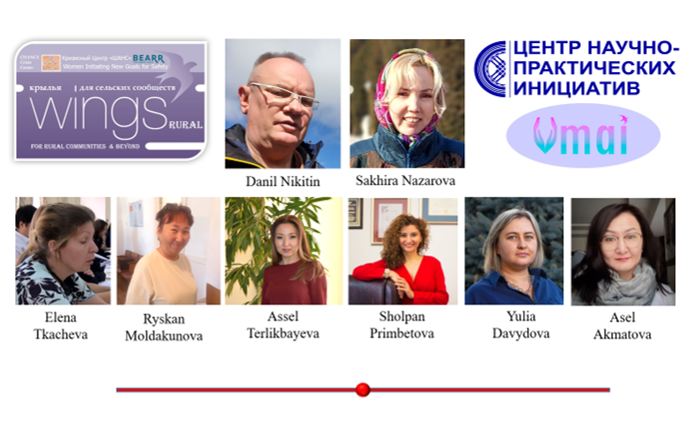

While preparing for the 16-day campaign against gender-based violence, journalist from Kyrgyzstan Sakhira Nazarova and head of the GLORI Foundation Danil Nikitin interviewed renowned researchers and practitioners in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan working on preventing gender-based violence and providing effective assistance to those at risk. The head of the Chance Crisis Center, Elena Tkacheva, together with her colleagues Asel Akmatova and Yulia Davydova, have been implementing the Rural WINGS project since July 2023. Ryskan Moldakunova, head of the NGO “Protecting the Dignity of Vulnerable Groups,” also takes part in the project. Assel Terlikbayeva and Sholpan Primbetova represent the Kazakhstan office of the Global Health Research Center of Central Asia and the Center of Scientific and Practical Initiatives, where work is in full swing to introduce a model of intervention to prevent gender-based violence among key groups in the Republic of Kazakhstan. In Kazakhstan, the project is called UMAI, named after the highly revered female deity, the benevolent patroness of children and women.

Sahira Nazarova (SN): Every year, activists conduct a 16-day campaign to protect victims of gender-based violence. Please tell us about its goals, characteristics, values, and why it is important and how relevant it is today.

Elena Tkacheva (ET): “16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence” is an annual international campaign that begins on November 25, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, and continues until December 10, Human Rights Day. The campaign was founded by activists at the first Women’s Global Leadership Institute in 1991 and continues to be coordinated annually by the Center for Women’s Global Leadership.

Yulia Davydova (YuD): The significance of this campaign is enormous. It is used around the world to call for the prevention and elimination of violence against women and girls. The campaign is still relevant today, unfortunately. These days, the whole world unites and directs its efforts towards the prevention and protection of women and girls.

SN: Are your current projects somehow align with this campaign?

Asel Akmatova (AA): We did not set such a goal for ourselves, it just so happened that the peak of our current activities on the project occurred these days, when the world is actively preparing for this campaign. At the beginning of the year, we at the Chance Crisis Center, together with colleagues at the GLORI Foundation, applied for support from the BEARR Trust to disseminate the WINGS intervention methodology in the rural areas of the Chui region, and our grant application was approved. This project is funded by the BEARR Trust Fund Small Grants Scheme. The GLORI Foundation works on monitoring and evaluation scope.

Ryskan Moldakunova (RM): The project covers the Moscow district of the Chui region of Kyrgyzstan, where the population is more than 100 thousand people. In the current conditions, when state social security needs support, the issues of providing effective assistance to women and girls affected by gender-based and family violence are acute. Niyazbek Egemkulovich Kozuev, akim of the Moskovsky district of the Chui region of Kyrgyzstan, supported our efforts and provides us with all the necessary support.

For reference: Moscow district of Chui region of Kyrgyzstan is an administrative-territorial unit formed in the 30s of the last century. The administrative center is the village of Belovodskoye. The population of the Moscow region is more than 100 thousand people, the predominant nationalities are Kyrgyz, Dungans and Russians. On the territory of the Moscow region there are several correctional institutions of ordinary, enhanced and strict security. Also here is the only educational colony for minors in the entire Chui region. There are no crisis centers for women and girls who have experienced gender-based and domestic violence in the region. There is also a severe shortage of psychologists and specialists trained in correctional interventions. In these conditions, increasing the capacity of employees of state and municipal social protection agencies is an urgent problem.

ET: The consequences of gender-based violence are serious, affecting the physical, mental and sexual health of women and girls. It affects women throughout their lives and is a leading cause of injury, disability and death among women, as well as negatively impacting the health and well-being of professionals providing services to affected women and girls. When providing assistance, a systematic approach is important, so our project consists of two phases: first, we prepare and conduct training for employees of state and municipal social protection bodies and activists of rural communities in the Moscow region, and after that we plan and provide external support for training participants for three months. The training is conducted using the WINGS methodology, which has been adapted to the conditions of rural communities. The results of the project are now being summarized and processed, we will be able to talk about them later.

For reference: The key components of the WINGS model are considered to be a chain of basic components: a short educational course, with the help of which a woman is explained the specifics of a particular type of gender-based violence, determining her level of victimization, i.e. screening her to determine her risk of becoming a victim of violence, motivating and working to improve her psycho-emotional state and social integration, creating a safety plan, referring her to appropriate service providers, setting goals for the near future, and providing the opportunity to be tested for various infections with mandatory gender-specific counseling. In English, this complex is called SBIRT, or Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment. All intervention components are equally important, they all require a lot of attention and are applied in strict sequence. Individual work is carried out with each woman; our psychologists and facilitators explain the concept of violence, types, differences, so that the woman clearly understands the terms that will be discussed during further meetings. The woman and the facilitator must be “on the same page” regarding what is black and what is considered white, only in this case the entire ladder, carefully built within the framework of the project, will be effective. The English acronym WINGS, consonant with the word “wings,” stands for Women Initiating New Goals for Safety. The intervention was originally designed and evaluated in the US by Dr Louisa Gilbert and her colleagues at the Columbia University Social Intervention Group with women who use drugs, and later successfully adapted and implemented in Kyrgyzstan, India, Georgia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan. WINGS has been translated into eight languages and is currently being widely used in six countries serving women from marginalized communities.

Assel Terlikbayeva (AT): Here in Kazakhstan, we use a computerized version of this intervention, which allows a woman to independently go through all the stages from the screen of a smartphone or computer. In our computerized version, we have interactive avatars, but there is no physical engagement of a facilitator, everything is designed for independent work.

Sholpan Primbetova (SP): Yes, while developing this computerized version, we realized that each brick in this ladder is unique and has its own place and purpose – for example, the goals that one woman has set for herself for the near future are often not even close to suitable for another. Some of the participants decided that the solution to the problem could be practicing self-defense skills with an experienced mentor, some turned to religion, some began to more purposefully look for work in order to have a constant income, and for some, it turned out to be a priority to restore connections with family and friends. And here’s what’s sincerely pleasing: none of the women participating in the project agreed to leave “everything as it is”, each of them decided to change something, minor or major, in their lives and in their relationships with their partners or with society.

AT: The same applies to the security plan. I agree with Mira Nurkatova, our colleague, who, together with Alena Rosenthal, coordinates the work of the project: drawing up and thoroughly working out this plan helps ensure that the woman participant knows where and who to call in case of danger, where to go in case of violence, and how behave and what to do to reduce the risk of violence or to protect yourself and your loved ones as much as possible if it cannot be avoided. Don’t forget, many of the project participants have children who are underaged. As a part of our UMAI project in Kazakhstan, we are integrating WINGS with another evidence-based intervention, Community that Cares (CTC). Much attention is being given to adapting this integrated intervention to community-based organizations that provide services to women who are victims of violence and who use substances or engage in commercial sex work. One of the main goals of our research-to-practice project is to address gaps in services for women from key populations by introducing innovative online digital interventions for women and active community engagement for system-level change.

SP: We partner with organizations that work directly with communities and people from key groups. In crisis centers and shelters for women who find themselves in difficult life situations, Kazakhstani women with different stories find temporary shelter. They all want to change their lives, forget about the past and learn to look into the future with optimism. Their lives are often challenging, they have complicated relationships with loved ones and relatives, and they may have nowhere to find support, participation and compassion. Participants in our unique project live in conditions of constant stigma, suffer from the breakdown of family relationships and social ties, from low legal literacy, from low self-esteem, from distrust of everyone and everything. They have practically only one resource left – public organizations working at the community level on a peer-to-peer basis with victims of gender-based violence, who now have the opportunity to use the unique integrated computerized model of behavioral intervention WINGS UMAI, which Assel Terlikbayeva mentioned. We, like our colleagues in Kyrgyzstan, will be able to talk about the results of the project later, but it is already obvious that the women participating in it note a significant decrease in violence of all types, incl. gender-based violence, intimate partner violence, and severe and less severe forms of physical and sexual violence, verbal abuse and psychological bullying, compared with data collected at the baseline assessment. Participants noted awareness of the risks of violence, significant reductions in substance use, improved skills in creating a safer environment for the provision of sexual services, as well as higher rates of referral to organizations that provide assistance to victims of gender-based violence. There is no doubt that after participating in the project, women’s condition and quality of life improves significantly, while confidence in public organizations is strengthened.

AA: By the way, please note: the attitude towards new preventive programs and models of providing assistance to women who have experienced violence is positive, and it does not differ much between employees of crisis centers and social workers from government social protection agencies. However, during our conversations, both of them for the most part confirmed that, whenever possible, they try and will try to use new and diverse programs and interventions that have been developed, adapted and piloted using scientific methodology and theoretical concepts. More than 80% of respondents noted that their organizations, both non-governmental and government, have memorandums of cooperation with research centers and universities. For example, my colleagues Yulia Davydova and Elena Tkacheva are not only highly qualified psychologists working at the Chance Crisis Center, but also conduct teaching and research activities at one of the leading universities in the country. Our long-term cooperation with the GLORI Research Foundation also testifies to the effectiveness of such interaction, and I am very pleased to hear that our colleagues in Kazakhstan also have this connection between science and practice.

RM: I agree, we all need unity and the ability to interact. Sometimes people ask me: why, despite our efforts, is there no less violence? To answer this question, I give the following analogy: many, many years ago, traffic rules were invented, agreed upon and implemented, the observance of which would have made it possible to significantly reduce mortality and suffering on the scale of all humanity. However, do we always follow these rules? No, despite pretty well equipped road inspection, discouraging fines, special schools where they teach safety rules — still there are victims, because not everyone and not always comply with these standards. It’s the same with violence: unfortunately, there are and will be those who violate universal human rules, who commit violence and who suffer from it, so we need innovative and scientifically based tools for prevention, behavioral correction and rehabilitation. Moreover, such tools that could be effectively used, including in the context of community organizations that, like my public association, work in remote areas and do not always have advanced technologies and a modern resource base.

Danil Nikitin (DN): What is the difference and what is the similarity in the appeal of victims to crisis centers and government agencies and service providers?

ET: What should women do in case of violence? It would seem that the answer is obvious: call the police, contact the social security authorities. But this seemingly traditional mechanism does not always work, and women either do not turn anywhere or to anyone, or go to crisis centers: the year is not over yet, and about six thousand women have already turned to our crisis center, including from socially vulnerable groups, that is, drug addicts, sex workers, those who have been released from prison. It is more convenient for them to seek help from crisis centers, where there are specialists who will listen to them and provide all possible assistance. Our experience also shows that for these women it is necessary to create alternative mechanisms of protection from gender-based violence. Help for these women should also be provided in community-based organizations, where staff can talk to these women as equals, without stigma and discrimination. They will understand each other better and together they will be able to find a solution to the problem that has arisen.

AT: Yes, I agree with Elena. There are features that need to be taken into account when providing services related to violence to women from socially vulnerable groups, including women who use psychoactive substances, women living with HIV and other related diseases, and sex workers. Von-profit community-based organizations working at the community level on a peer-to-peer basis take these features into account, since they are an important link in the chain of service delivery. This is a matter of trust and efficiency of the services provided. However, these community-based organizations need state support and the ability to provide a package of social services guaranteed by the state in state crisis centers. Our project in Kazakhstan aims to address these gaps in access to government social services for vulnerable women through community-based organizations.

SN: How would you score the work being done in our countries to prevent gender-based violence on a scale from 1 to 10? Why did you give this assessment? What else can be done to make this score higher?

AA: Thanks to comprehensive work to eradicate violence, these topics are no longer taboo; the increase in detection suggests that not all women are afraid, and rightly so. The situation is paradoxical: it seems that numerous international conventions and memorandums have been signed at the country level, campaigns, conferences and trainings are held, a lot of money is spent, and everything seems to be fine at the macro level. But the existing patriarchy does not want to retreat, and as soon as it comes to the micro level, that is, each individual woman and each individual case, it suddenly turns out that the gaps in the service system, in the system of protection from violence, in the security system for each of us are still huge. Taking this into account, I would give it 4 points on a 10-point scale. And for this assessment to be higher, it is necessary to get rid of patriarchy, which is entrenched in our thinking and our way of life, and to get rid of it at the legislative level and achieve real gender equality. Elena mentioned women, including those who are subject to stigma and discrimination due to their belonging to certain social groups, but to what extent does the country platform for providing assistance to women take into account their characteristics? It is poorly taken into account, the interior itself inside police stations or social security agencies is not conducive to a private confidential conversation, there are no conditions for this, and yet often women who seek help have a strong feeling of guilt, they have self-stigmatization that needs to be worked through. Women survivors of violence complain about the callousness of law enforcement officers, low levels of empathy, and the lack of female officers, which affects trust in the work of government agencies. Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen efforts to train police officers on gender topics, but for now this is exactly the assessment of the existing system.

ET: I’d give it two out of ten. It is a huge failure of the state that they did not pay attention to the need to train social workers in the skills of providing assistance in cases of domestic violence. Yes, there are job descriptions, there are training manuals, but in practice, stigma and discrimination do exist. In order for this score to be higher, it is necessary to introduce certain gender-specific tests that would be mandatory for every person who wants to take a position in government agencies. After all, now all civil servants undergo testing to assess their professional knowledge and skills, so why not oblige them to take tests that, already at the stage of applying for a job, would identify those who are prone to misogyny and tolerant of violence and stigma and discrimination? The law on domestic violence must be revised; it requires by-laws and approved standards to ensure the provision of assistance to women who have experienced violence, but today this is all missing. By the way, updated guidelines for medical documentation of violence, torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading types of treatment and punishment are currently being developed and are being prepared for implementation. These guidelines will replace what was formerly known as Istanbul Convention form. When these guidelines and innovations are adopted, when they start functioning and when detailed procedures for managing screening and documenting cases are outlined, I will be ready to reconsider my negative assessment and the low score. By the way, we at crisis centers are ready to assist in drawing up procedures and training motivational interviewing skills for those doctors and law enforcement officers who will be in direct contact with women who have survived violence – we ourselves practice this within the framework of the WINGS model and are ready to train others.

RM: Due to the officially reported high rates of gender-based violence and the prevalence of migrant workers, it is important to explore the possibility of introducing interventions in areas bordering Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. There are currently no migrant-specific interventions to combat gender-based violence. If such an intervention were developed and tested in Kyrgyzstan, it would benefit communities affected by problems common to internal and external migrants in both sending and receiving countries, including Russia. In this case, I’ll give it a high score, but for now I’m assessing it for 3 out of 10.

DN: How applicable is the WINGS SBIRT model discussed today for projects aimed at preventing human trafficking and implementing a country referral mechanism?

AA: This is an excellent intervention model that, with appropriate adaptation, can be used to help those who have been trafficked. Of course, this can be done after the completion of investigative actions, at the rehabilitation stage, when a person needs to decide on goals for the near future, assess his capabilities, strengthen the so-called circle of social support and begin to build his life. In order for crisis centers to become part of this system of providing assistance to victims of human trafficking, of course, it is important to think through the issue of allocating resources so that we can effectively carry out this work.

For reference: In 2013, only two community organizations, one in Bishkek, the other in Osh, introduced services according to the WINGS model, and in 2023 there are already 18 of these organizations in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. Chance Crisis Center and the GLORI Foundation with the support The BEARR Trust Fund Small Grants Scheme are working to ensure that the WINGS model is included in the state standard and becomes the basic platform for all social workers who have become an important link in the system of providing assistance to people who have survived violence. Active work is also underway abroad: for example, Dr Tina Jiwatram Negron from Arizona State University, who took an active part in piloting this intervention model in Kyrgyzstan, is working on implementing it in at-risk communities in Pakistan and US.

SN: Changes to the Law “On NGOs” and the Criminal Code, initiated by a group of deputies, are currently being discussed, which provide for the introduction of the concept of “foreign representative” (analogous to a foreign agent in Russian legislation). In your case, how big is the risk that by receiving funding from foreign charitable foundations and implementing projects, you will be associated with foreign agents?

ET: If these changes are adopted, our work will not be affected, and we will continue to seek funding from a variety of sources. The fact that it is the state that is obliged to protect people from violence and finance the work of crisis centers was announced back in 1995, but this has not happened yet; there is still not a single state crisis center in the country. We were ready to become a municipal crisis center, but this never happened. We survive as best we can, including through the state social order system. But the state social order cannot solve all the issues and cover all the needs, so I consider receiving support from donors, philanthropists, and international organizations to be a forced measure that we are forced to resort to.

AA: If the proposed amendments help resolve issues related to violence and corruption, if as a result of the introduction of these changes the environmental situation in the country improves, then we will welcome it. However, in its current form, it looks like an instrument of pressure that could lead to additional control by the state. Our current work is largely based on building effective interaction with state and municipal authorities, but if the proposed amendments are adopted, this interaction may be disrupted: which government agencies will want to deal with so-called agents? And the lack of interaction will lead to negative consequences, and those who need timely assistance from highly qualified professionals, to whom we consider ourselves, risk not receiving it at all or receiving it in insufficient quantities.

SP: In Kazakhstan, on the website of the State Revenue Committee, a list of people and organizations has appeared, similar to the Russian register of “foreign agents”. The full list of defendants is available in the interactive table. In the first publication there are 240 people and organizations, among which are independent media, journalists, human rights organizations and NGOs – for example, our Center for the Study of Global Health in Central Asia is also included in the list. This is just a kind of list of public organizations that receive grants from abroad. The legislation of the republic does not yet impose any restrictions on those on the list, so we will consult with lawyers and monitor the situation.

YuD: Yes, I agree with my colleagues, these risks must be taken into account. We will also be calculating various options, thinking through the strategy for the development of our crisis center. If we speak retrospectively specifically about today’s work, then even taking into account the listed risks, we would still have turned to the BEARR Trust and would still have implemented this wonderful Rural WINGS project, from which the state has nothing but benefit. If I could advise something to the initiators of these amendments, I would say briefly: no one needs them, and there will be no benefit from them. Better yet, let’s all work together on issues of developing and strengthening partnerships with the non-governmental sector, let’s adopt strategic documents and laws with a concept for the development of civil society for the next decade.

Danil Nikitin: Thank you very much, colleagues, for sharing your thoughts and all the hard work you’re doing — the 16-day campaign is approaching, so let me wish all of us peace and patience.

Contact details:

Elena Tkacheva: chance-cc@mail.ru

Assel Terlikbayeva: Assel.Terlikbayeva@ghrcca.org

Yulia Davydova: yulyadavydova@yandex.ru

Sholpan Primbetova: Sholpan.Primbetova@ghrcca.org

Asel Akmatova: asel.art.initiatives@gmail.com

Ryskan Moldakunova: m.r.elmart@mail.ru

Sakhira Nazarova: nazarova.kg@gmail.com

Danil Nikitin: Danil.Nikitin@glori.kg