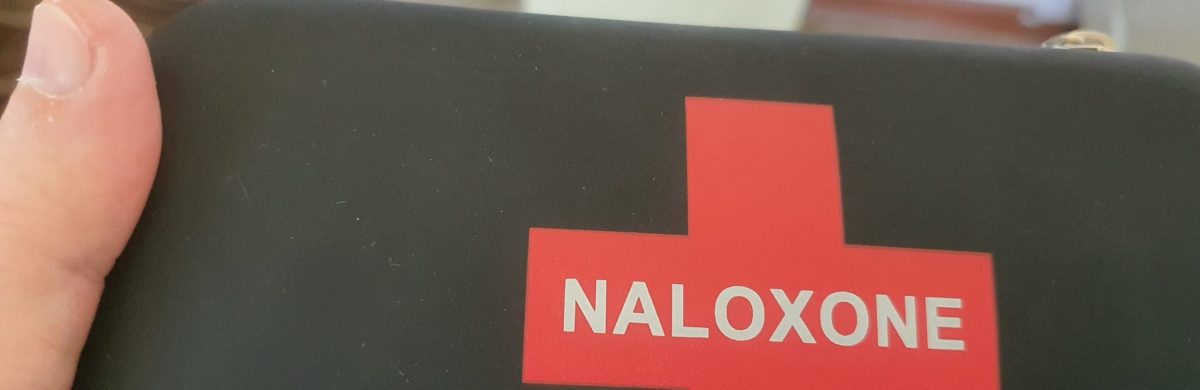

“We found our neighbor in the playground recently, he was almost dead, all pale. We called the ambulance, but really were not sure he would survive. Good guy actually, has been injecting for several years, his parents tried to cure his addiction but relapse happens sometime, unfortunately. At that time, he would hardly survive if his friend did not inject him Naloxone into the shoulder, luckily he had an ampule with him. Soon he started murmuring something, lips turned pink again, it was kind of a magic recovery, I witnessed it with my own eyes”. This was a real-life experience shared by a woman living in an apartment house in the center of Bishkek. Similar stories can be heard not just in Bishkek but also in Osh, Karasuu, Uzgen, and each of them refers to Naloxone. This medication often appears critically important and most effective substance that saves lives of people who are not able to properly manage their dose of heroin and suffer from overdose.

“We found our neighbor in the playground recently, he was almost dead, all pale. We called the ambulance, but really were not sure he would survive. Good guy actually, has been injecting for several years, his parents tried to cure his addiction but relapse happens sometime, unfortunately. At that time, he would hardly survive if his friend did not inject him Naloxone into the shoulder, luckily he had an ampule with him. Soon he started murmuring something, lips turned pink again, it was kind of a magic recovery, I witnessed it with my own eyes”. This was a real-life experience shared by a woman living in an apartment house in the center of Bishkek. Similar stories can be heard not just in Bishkek but also in Osh, Karasuu, Uzgen, and each of them refers to Naloxone. This medication often appears critically important and most effective substance that saves lives of people who are not able to properly manage their dose of heroin and suffer from overdose.

In Kyrgyzstan, the S-O-S (“Stop Overdose Safely”) project gets launched that focuses on innovative approaches to opioid overdose prevention. The initiative is a part of the Joint UNODC-WHO Programme on Drug Dependence Treatment and Care, Re-Integration and AIDS Prevention.

Sahira Nazarova, the Osh-based journalist, interviewed the project team.

Sahira Nazarova: Please tell more about the project.

Kubanychbek Ormushev: Naloxone saves lives, it has been proved by multiple research and does not need to be supported by additional evidence. The key goal of the project is more practical – we’d like to develop a model for saving lives through expanding the availability and accessibility of community management of opioid overdose, including training and take-home naloxone. The final target population are people likely to witness opioid overdose, including peers and family members. The Kyrgyz-based working group includes Republican Narcological Center, GLORI Foundation, Partnership Network Association, and Harm Reduction Network Association.

Sahira Nazarova: What’s the prevalence of overdose in Kyrgyzstan?

Danil Nikitin: It’s hard to estimate the overdose prevalence in Kyrgyzstan. Availability of data regarding the rates of fatal and non-fatal overdose among PWID in Kyrgyzstan is generally limited, as centralized data collection and reporting systems on overdoses are underdeveloped. There are an estimated 25,000 PWID in Kyrgyzstan. The most prevalent drugs in Kyrgyzstan are opioids and cannabis.

Top row, left to right: Danil Nikitin (GLORI Foundation), Aibar Sultangaziev (Partnership Network Association), Almaz Asakeev (Antistigma NGO), Sergei Bessonov (Harm Reduction Network Association in Kyrgyz Republic), Kubanychbek Ormushev (|National Programme Officer, UNODC Programme Office in the Kyrgyz Republic) Lower row: Alisa Osmonova (Antistigma NGO) and Tatiana Musagalieva (Harm Reduction Network Association in Kyrgyz Republic)

Sergei Bessonov: About 70,000-100,000 people die from opioid overdose each year. At the global level, overdose is the leading cause of avoidable death among people who inject drugs. According to the official statistics of the National Health Information Centre of the Ministry of Health of the Kyrgyz Republic that the Harm Reduction Association team announced at the recent International AIDS Conference in Amsterdam, the number of deaths resulting from drug overdoses decreased by almost a quarter between 2010 and 2011, down to 64 fatal overdoses. Among PWID, the vast majority are thought to inject heroin (corresponding to 95% of registered drug users), imported from Afghanistan.

Aibar Sultangaziev: Drug-related mortality is significantly underreported in Kyrgyzstan due to the stigma associated with drug consumption among families. This leads to underestimation of the resources and services needed in order to provide overdose prevention services, as well as information to families on how to address cases of drug overdose.

Tatiana Musagalieva: Prevalence of overdose in women who use drugs can be monitored through the data collected in WINGS of Hope project. Experiencing overdose “ever” was reported by 46% of the project women participants, and 6% overdosed in the past 3 months. In the framework of project, the women participants also shared that 45% of their peers died from overdoses.

Sahira Nazarova: What can we do to prevent such high mortality rates?

Alisa Osmonova: The administration of opioid antagonists, the most prominent of which (in the acute care setting) is naloxone, is recommended to quickly reverse opioid effects. Naloxone is widely available in medical facilities in many countries, but recently efforts have been made to expand naloxone availability to non-medically trained people.

Sahira Nazarova: Is it true that a similar model will be implemented by you in our country?

Alisa Osmonova: Yes, our project will focus on training lay people who are likely to witness an opioid overdose. They will be trained in overdose recognition and response (e.g. rescue breathing). The critical component of the training will be how to administer naloxone.

Aibar Sultangaziev: By the way, the project is conducted not only in Kyrgyzstan, but also in Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Ukraine.

Sahira Nazarova: That’s excellent. Who is the Principal Investigator of this exciting project?

Danil Nikitin: The Principal Investigator is Dr Paul Deitze of Burnet Institute in Australia. Paul is providing overall supervision in close cooperation with Ms Anja Busse of Viena-based UNODC office, and Mr Dzmitry Krupchanka of the World Health Organization.

Sahira Nazarova: I am sure that there were several trainings applied at the preparatory phase – please tell more of them.

S-O-S training on overdose management and Naloxone application. Kiev, Ukraine. October, 2018.

Alexandra Kachkynalieva: Yes. Sure. The most recent training event occurred in Kyiv in October 2018. At this three-day event, participants representing Ministries of Health, civil society and research centers from all project countries as well as international experts in the field of overdose management reviewed the protocol and discussed the next steps needed for its implementation at the country level, including the selection of sites and national coordination mechanisms. Participants were also involved in designing and validating the most effective evidence-based methodologies that will be applied for training people who most likely witness overdose. The trainings was conducted by Kirsten Horsburgh from Great Britain.

Sahira Nazarova: I heard of Kirsten Horsburgh’s work, she is a Strategy Coordinator on Drug Death Prevention at the Scottish Drug Forum. What groups are mostly exposed to the risk of overdose?

Almaz Asakeev: The vast majority of overdoses are accidental. Four out of every five deaths from overdose are preventable. There are several behavioral risk factors for overdose. Risk is increased when opioids are injected (especially intravenously). Risk is high when alcohol or other sedative drugs (e.g. benzodiazepines) are consumed along with heroin. People whose tolerance is reduced and who are using alone, with no one around to intervene, are also exposed to high risk of overdose.

Sergei Bessonov: Tolerance is significantly reduced after periods of abstinence or reduced illicit opioid use. As a result, return into the community after a stay in a drug-free institution or the end of bein involved in drug use disorder treatment is characterized by increased risk of overdose. These situational risk factors include release from prison, discharge from residential treatment, or end of detoxification course.

Alexandra Kachkynalieva: The most striking evidence of these effects of changes in tolerance is the concentration of overdose deaths among prisoners on release. For example, of prisoners with a previous history of heroin injecting who are released from prison, an estimated 1 in 200 will die of a heroin overdose within the first 4 weeks of release. This is approximately 10 times the mortality rate of general prisoners being released (who themselves have an increased risk) and approximately 100 times greater than an age-matched general population.

Sahira Nazarova: Is Naloxone the medication that can help people exposed to the risk of overdose? Since most overdoses are witnessed by a friend or family member, is it true that if a friend or family member had access to naloxone, he or she may be able to reverse the effects of opioid overdose, while waiting for medical care to arrive?

Venera Januzakova: Naloxone is on the WHO List of Essential Medicines, and is licensed for intravenous, intramuscular, or subcutaneous injection. The efficacy of naloxone in the treatment of opioid overdose is considered to be largely independent of the route of administration. In drug-use community setting, naloxone is typically administered parenterally as an intramuscular injection, since establishing intravenous access may be difficult. While naloxone administered by bystanders is a potentially life-saving emergency interim response to opioid overdose, it should not be seen as a replacement for comprehensive medical care.

Aibar Sultangaziev: There is some evidence from studies undertaken in the United States and Russia for the cost-effectiveness of community-based naloxone provision. The cost-effectiveness of community-based naloxone provision estimated by these studies is well within the bounds of what is considered reasonable for judging cost-effectiveness of many common medical therapies.

Sahira Nazarova: Please tell more about the working flow of the project.

Tatiana Musagalieva: The project runs with finance support from the UNODC and WHO. It is the UNODC and WHO Guidelines that we’ll be following while designing overdose-prevention and Naloxone-use trainings. These trainings are primarily for people likely to witness an overdose. To these people we will distribute emergency kits with neatly packed ampoules of Naloxone, syringes, alcohol swabs, and latex gloves. No less than 4000 people will benefit from the project services.

Kubanychbek Ormushev: The guidelines that Tatiana mentions, were published by WHO on 4 November 2014. They are evidence-based and aim to reduce the number of opioid-related deaths globally. The guidelines recommend countries expand naloxone access to people likely to witness an overdose in their community, such as friends, family members, partners of people who use drugs, and social workers. In most countries, naloxone is currently accessible only through hospitals and ambulance crews who may not manage to get help to the people who need it fast enough.

Danil Nikitin: As we mentioned earlier, the project targets include saving lives by making naloxone and training on overdose management available to all people likely to witness an overdose, including peers and family members. The initiative sets a global implementation target of 90:90:90 as a joint point of reference: 90% of the relevant target population should be trained in overdose risk and emergency management; 90% of those trained should carry take-home naloxone; and 90% of those who have been given a naloxone supply should use naloxone at overdoses they witness.

Sahira Nazarova: Thank you. When the project gets launched, and when do you plan to complete it?

Kubanychbek Ormushev: We are finishing the preparatory phase, and it is March 2019 that we plan to start field activities with drug users. These field activities are likely to have been lasting through the Fall. All project activities will take place in Bishkek, Kant and Sokuluk.

Sahira Nazarova: Thank you so much for all the important information that you kindly shared. I wish you great success with the project that really creates a safer environment and opportunities for people who are in the most-at-risk groups.

—

March 2019

Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan